The Higgs Boson

The Higgs: A decade in review

The particle, now called the Higgs boson, first appeared in a 1964 scientific treatise by Peter Higgs. At that time, physicists were working to explain the weak force (one of the four fundamental forces of nature) using a framework called quantum field theory.

| The 1964 Peter Higgs paper first predicted the existence of what would be known as the Higgs boson., 1 |

The discovery of the Higgs boson was a triumph. Not only for the physicists at CERN’s LHC but also for the scientific imagination.

CERN:

CERN (Conseil Européen pour la Recherche Nucléaire) is the world’s most famous laboratory for particle physics. WWW was invented here, and then later, the Higgs boson. CERN was founded in 1954 on the border between Switzerland and France. Currently, it has more than 10,000 people working in CERN from 80 countries. Iranians and Americans, Palestinians and Israelis, Pakistanis and Indians are collaborating on studying subatomic materials. The operating cost of the LHC runs to about a billion Swiss Franc per year. Hundreds of meters below their office, protons run at incredible energy of 14 TeV (teraelectronvolts) accelerated by the Large Hadron Collider (LHC), which was designed to find the mass of elementary particles, mysterious dark matter.

|

|---|

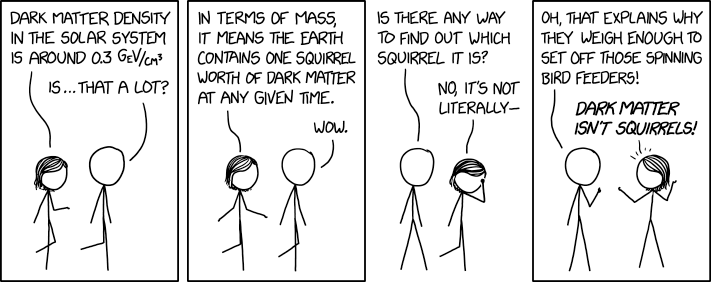

| To detect dark matter, we just need to build a bird feeder that spins two squirrels around the rim in opposite directions at relativistic speeds and collides them together., 2 |

LHC:

The CERN accelerator complex is a series of machines with ever-increasing energy. Each engine accelerates a jet of particles to given energy before injecting the jet into the next device in the chain. This next machine makes the beam even higher in energy. The LHC is the last link in this chain where rays reach their highest energy. Inside the LHC, the particle is travelling at nearly the speed of light before the two beams collide. The jets travel in opposite directions in separate jet tubes. The two tubes are kept in an ultra-high vacuum. They are guided around an accelerating ring by a strong magnetic field maintained by superconducting electromagnets. Below a specific characteristic temperature, some materials become superconducting and can no longer resist the passage of electrical current. Therefore, the electromagnets in the LHC are cooled to 2 Kelvin to take advantage of this effect. The accelerator is connected to a huge liquid helium distribution system that cools the magnets and other utilities.

| The LHC is the last ring (dark blue line) in a complex chain of particle accelerators. The smaller machines are used in a chain to help boost the particles to their final energies and provide beams to a whole set of smaller experiments, which also aim to uncover the mysteries of the Universe. , 3 |

Particles:

Quantum field theory describes the microscopic world of particles very differently from everyday life. Fundamental “quantum fields” fill the universe and dictate what nature can and cannot do. In this description, every particle can be represented by a wave in a “field”, similar to a ripple on the surface of a vast ocean. When particles interact with one another, they exchange “force carriers”. These force carriers are particles and can also be described as waves in their respective fields. For example, when two electrons interact, they do so by exchanging photons – photons are the force carriers of the electromagnetic interaction.

Another vital element of this image is symmetry. Just as a shape can be called symmetrical if it does not change when rotated or flipped, the exact requirements are placed on the laws of nature. For example, the electric force between the charge carriers of a particle will always be the same whether the particle is an electron, a muon, or a proton. Such symmetries form the basis and determine the structure of the theory.

|

|---|

| Particles of the Standard Model of particle physics., 4 |

Higgs Mechanism:

Before the prediction of the Higgs particle, the Standard Model was incomplete. Quantum field theory with gauge invariance (symmetry which leads to conservation of a quantity) successfully understood electrostatic and strong forces. But till the 1960’s it was unable to create a gauge invariant theory for the weak forces. The symmetry required W and Z bosons to be massless but studies predicted they had a non-zero mass. Other promising solutions required particles named Goldstone bosons to exist, which were also proved to be not existing. This was a major issue for particle physicists. So there were two options - either gauge invariance was an incorrect approach or something unknown was giving mass to W and Z bosons in a way which did not create Goldstone bosons. Yoichiro Nambu recognised spontaneous symmetry breaking, in the late 1950s, that would occur under certain conditions. In 1962, physicist Philip Anderson suggested that symmetry breaking could provide an answer to gauge invariance in particle physics. He suggested that the Goldstone bosons which result from symmetry breaking would be absorbed “under some condition” by the massless W and Z bosons. This means Goldstone bosons would not exist and W and Z bosons could gain mass, solving both problems. Following these papers, three groups of researchers developed these theories independently and reached similar conclusions for all cases. This came to be known as the 1964 PRL symmetry breaking papers. The electroweak symmetry would be broken if a field existed throughout the universe. This field came to be known as the Higgs field and the mechanism by which it led to symmetry breaking as the Higgs mechanism. A key feature of the necessary field is that it would take less energy for the field to have a non-zero value than a zero value, unlike all other known fields, therefore, the Higgs field has a non-zero value (or vacuum expectation) everywhere. In theory, this non zero value could break symmetry and proved consistent with the gauge invariant theory. This fitted like the missing piece of the Jigsaw puzzle.

Higgs Field:

“Higgs Field” exists throughout space, and it breaks some symmetry laws of the electroweak interaction, triggering the Higgs mechanism. It therefore causes the W and Z gauge bosons of the weak force to be massive at all temperatures below an extremely high value. When the weak force bosons acquire mass, this affects the distance they can freely travel, which becomes very small, also matching experimental findings. Furthermore, it was later realized that the same field would also explain, in a different way, why other fundamental constituents of matter (including electrons and quarks) have mass.

|

|---|

| There are a bunch of different fields; each field has different properties and excitations, and they are different depending on the properties, and those excitations we can think of as a particle, 5 |

Unlike all other known fields, such as the electromagnetic field, the Higgs field is a scalar field and has a non-zero average value in a vacuum. There was not yet any direct evidence that the Higgs field existed, but even without direct proof, the accuracy of its predictions led scientists to believe the theory might be true. The existence of the Higgs field became the last unverified part of the Standard Model of particle physics and for several decades was considered “the central problem in particle physics”.

Search and Discovery:

Although the Higgs field would exist everywhere, proving its existence was far from easy. In principle, it can be proved to exist by detecting its excitations, which manifest as Higgs particles (the Higgs boson), but these are extremely difficult to produce and detect due to the energy required to produce them and their very rare production even if the energy is sufficient. The importance of this fundamental question led to a 40-year search and the construction of one of the world’s most expensive and complex experimental facilities to date, CERN’s Large Hadron Collider, in an attempt to create Higgs bosons and other particles for observation and study. On 4 July 2012, the discovery of a new particle with a mass between 125 and 127 GeV/c2 was announced; physicists suspected that it was the Higgs boson. According to the Standard Model, Higgs boson has a zero spin, even parity, no electric charge and a mass of 125.35 ± 0.15 GeV/c2. It is very unstable and decays immediately into other particles.

|

|---|

| The Standard Model, 6 |

Progress on Boson:

Some models have proposed versions of Higgs that have different properties than the boson we know. The Higgs boson, discovered in 2012, has no spin and no charge, but other Higgs particles may have different properties. Other models suggest that one type of Higgs interacts with heavy particles and another with light particles. Alternatively, the Higgs boson we see may be a composite of several different particles. Some phenomena that can explain the additional Higgs boson are dark matter, neutrino oscillations, the mystery of neutrino mass, and why there is a matter-antimatter imbalance in the universe. Specific theories predict that dark matter interacts with ordinary matter by exchanging Higgs bosons. In this case, collisions that produce Higgs particles can also produce dark matter particles. Experiments with Colliders show no anomalous particles, suggesting their presence due to the lack of energy after the collision, which is yet to be investigated.

-

https://journals.aps.org/prl/abstract/10.1103/PhysRevLett.13.508 ↩

-

https://xkcd.com/2186/ ↩

-

https://cds.cern.ch/record/2684277 ↩

-

https://home.cern/science/physics/standard-model ↩

-

https://www.quantamagazine.org/what-is-a-particle-20201112/ ↩

-

https://www.quantamagazine.org/a-new-map-of-the-standard-model-of-particle-physics-20201022/ ↩