Measuring Fireballs

How do we know the dimensions of stars? Rediscover them yourself using simple physics.

When we look to the skies on a bright day, there is one magnificent and brilliant body radiating its kind warmth onto our planet in just the right amount to sustain life. The physical extent of this luminous companion in our skies is so vast that we simply can not comprehend it with our puny logarithmic human brains. Yet it is these puny brains that have somehow managed to estimate the size of the Sun with remarkable precision. Obviously there was no one with a measuring tape or weighing scale to actually take these measurements. So how did we do it?

The first ingredient in measuring the Sun would be to find out how far away it actually is. One of the first estimates was made by using an interesting coincidence. In a solar eclipse, it is very apparent that the diameters of the Moon and the Sun are in proportion to their distances from Earth. Aristarchus of Samos estimated that the Sun was 20 times further than the Moon. While he had the right idea, he did not measure the angle between the Sun, the Earth and the Moon with enough accuracy to perform the triangulation. In these scales, the tiniest of errors blow up, and despite being only around $ 2 \deg $ away, the Sun is actually around 400 times further from the Moon, a factor of 20 from Aristarchus’ estimate.

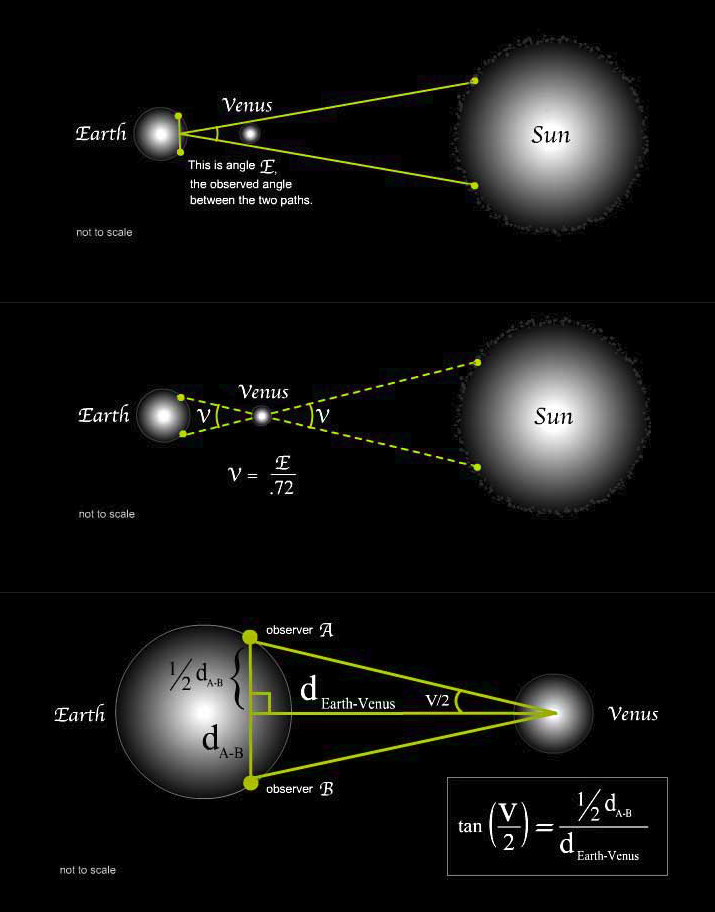

A significantly more precise measurement was made when we determined a method to measure the parallax of the Sun better. The parallax is often used to find the distances to astronomical objects from Earth. For the uninitiated, close one of your eyes. If you switched the closed eye, you will notice that you’re seeing a slightly different image. This is called parallax, and it allows us to perceive depth. If we use proper geometry, we can actually measure this depth or distance. Edmond Halley proposed using the transit of Venus to measure the solar parallax. In 1769, scientists collectively took a field trip across the globe, to Mexico, Russia, Norway, Tahiti and Canada. They measured the solar parallax to be around $ 8.48’’ $, a remarkably precise estimate in comparison to the accepted value today. Today, radar and spacecraft telemetry has given us the currently accepted value of $ 8.794’’ $.

|

|---|

| From Kepler’s Law, we know that the distance between Earth and Venus is 0.28 times the distance between the Earth and the Sun, 1 |

From the parallax, we find that the value of the astronomical unit, or the distance between the Earth and the Sun is around $ 1.495 \times 10^{11} $ m. Cavendish had carefully managed to determine the value of the universal gravitational constant. Now we can use Kepler’s 3rd Law to solve for the mass of the Sun.

Since we’re doing a back of an envelope calculation, we’ll use the classy approximation of $ 1 yr = \pi \times 10^7 s $

Go ahead, pop that calculation into a calculator and see for yourself. You’ve just weighed the Sun! However, as the Sun sets and sky grows dark, we enter a different realm. Yes, the moon is the brightest object in the sky now. However, something else interests us. Much, much further away are numerous little pin-pricks of light scattered across the sky. It is fairly easy to determine exactly how far away these stars are, now that we know the principles of parallax. Yet parallax itself is a tricky measurement to determine precisely. We have to wait for a while to get sufficiently far from the location of the first measurement. Not to mention that the measurements themselves have to be precise. To help us with this, we have sent out spacecrafts like the Hipparcos mission and the Gaia mission, both of which have helped the list of known parallaxes to grow exponentially. However, our previous method to determine the mass fails here. Our planet does not orbit the star in question and we have to resort to other ways to find the mass of the stars.

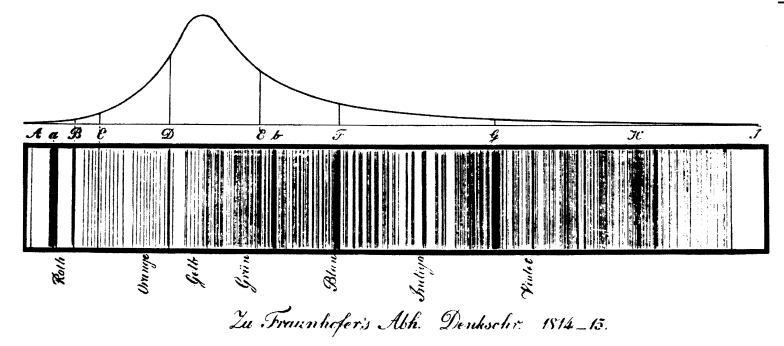

Our good friend Aristarchus and Anaxagoras believed that the Sun was one among many stars in the sky. Unfortunately, they had no source to back their claims. It was not until the 19th century that humanity managed to find solid proof that the Sun was indeed a star. Joseph von Fraunhofer invented the spectroscope in 1814. He neatly marked out 574 lines in the solar spectrum. Gustav Kirchoff and Robert Bunsen also managed to determine what exactly these spectra were. They managed to find a connection between these spectral lines and chemical elements. If an element absorbed at a certain wavelength, it would leave behind a dark line in the spectra. These lines were unique for all elements and were used as chemical tracers to identify the composition of objects. Kirchoff showed that the solar spectral lines corresponded with bright emission lines of incandescent vapors in his lab. Anders Angstrom and others went on to show that the Sun was majorly made of hydrogen. This method was extended to stars much further away by Angelo Secchi who measured around 4000 stellar spectra and was conclusively able to find that the Sun was a star just like any other.

|

|---|

| Fraunhofer’s solar spectral lines, 2 |

We now have sufficient information to estimate the masses of stars. We know it is made majorly of hydrogen - a very simple element consisting of nothing more than a proton and an electron. We already know the mass of hydrogen, so all we need to do is find out just how many individual atoms there might be in a star and we’re set. Stars however, are diverse objects. There are numerous classes and types of stars. Even the same star varies significantly as it ages. A first assumption to make would be to assume that we have a generic main sequence star - one that’s burning hydrogen for fuel. Let’s make some more reasonable simplifying assumptions - that a star has a uniform density, a uniform temperature, $ T $ and a radius of $ R $. The major force holding together particles in a large celestial object is gravity, which follows an inverse square law. The virial theorem is a powerful general equation which relates the time average of the kinetic energy with the potential energy of the system. For inverse square systems, the virial theorem equation reduces to:

We already know the expression which resides upon the left side of the equation. The kinetic energy possessed by particles in a star would be a result of their thermal motion. The equipartition theorem gives us the exact relation we’d like to use here. The right side is also fairly familiar, it is simply the gravitational potential energy experienced by the atoms in the star. If we assume that there are $ N $ atoms in the star and the mass of the atom to be $ m $, the following equation follows:

However, that quantity on the bottom of the right hand side of the equation - the stellar radius is actually fairly difficult to determine. One of the ways you could go about it is to assume the star to be a black body and use Stefan-Boltzmann’s equation. However, to do this, you would need other quantities like the luminosity and temperature of the star. There is a simpler method we can use if we avoid this quantity altogether and replace it by a quantity that’s easier to determine - the average distance between protons in a star. This can be found by doing:

Now if we return to the expression we obtained from the virial theorem, multiply and divide by $ hc $ and simplify, we get:

The factor on the right is filled with our favorite familiar constants - $ G $, $ h $, $ c $ and a guest appearance from the mass of the proton. If you crank the numbers, it evaluates to $ 2.21 \times 10^{57} $. The first factor, however, is a slightly tricky one to determine. However, as you’ll see, this term is fairly small. The average distance between protons should be of a few orders higher than a hydrogen atom’s radius. The effective temperature of stars is of the order of thousands or tens of thousands from stellar evolution models. The rest of the values are well-known constants. You will see that this term stays below a few hundreds even when you plug in extreme values from our assumptions. Considering we know how many atoms are there approximately, all we need to do is multiply the mass of one atom with it. We’ve got fairly good estimates for the masses of stars!

-

Image from Exploratorium ↩

-

Image from Solar Astrophysics by Peter Foukal ↩